The Apple That Changed Everything

How Newton unlocked the code of reality

Ask someone to name the most influential scientist in history, and you’ll usually hear one of two names: Einstein or Newton.

Both reshaped our understanding of the universe. But what most people don’t know is that Newton spent the last three decades of his life not in a laboratory but inside the Tower of London, overseeing England’s currency.

In 1696, he was appointed Warden of the Royal Mint. What followed was a national overhaul of the money system, led by a man who believed that, just like nature, a monetary system should obey fixed laws.

1690s Currency Crisis

England’s economy was crumbling in the 1690s. Nearly one in five silver coins in circulation was either counterfeit or clipped down to a fraction of its proper weight.

Trust in money was breaking down. The Nine Years’ War with France was bleeding the treasury dry, while heavy taxes to fund it crushed merchants and ordinary folk alike.

Trade sputtered as reliable coins vanished, and even tax collectors struggled to gather enough valid currency.

In 1695, Parliament, desperate to restore order, launched the Great Recoinage, a massive plan to replace every worn or forged coin with new, standardized ones—a logistical nightmare in an era of hand-struck money and rampant corruption.

Into this mess stepped Sir Isaac Newton in 1696, handed the role of Warden of the Royal Mint by his old friend Charles Montagu, then Chancellor of the Exchequer—the equivalent of England’s Treasury Secretary.

Newton was a scientist, not a financier—his world was telescopes and gravity, not coin presses. The wardenship was meant to be a cushy sinecure, a well-paid political favour for loyal insiders to collect a salary and stay out of the way. Newton had no interest in that.

He brought the same discipline and precision that had defined his scientific career into the Mint, focusing solely on rebuilding the system from the inside out.

Newton and the Great Recoinage

Newton arrived at the Tower of London in April, 1696 and stepped straight into the middle of a collapsing currency system.

The Mint was overwhelmed. Silver had to be recalled, melted down, reweighed, restruck, and pushed back into circulation before the economy ground to a halt.

Newton took control. He set up auxiliary mints across the country, enforced strict weight and purity standards, and rooted out internal corruption.

He personally tracked counterfeiters, questioned witnesses, and built cases strong enough to hold up in court. Most of the real work didn’t happen behind a desk, but rather in the field.

By the end of it, 28 coiners had been condemned. In 1699, he was promoted to Master of the Mint, giving him full control over coin production, contracts, and policy. He left Cambridge shortly after to focus entirely on the job.

“Newton brought order to chaos. He managed over the next 30 years to recall all coins in circulation and replace them with a more secure coinage.”

— Economic historian John Craig, The Mint (1953)

This wasn’t merely a ceremonial post anymore. Newton restructured the Mint from top to bottom and personally oversaw the removal of forged currency from circulation.

Every clipped or underweight coin was taken off the street and replaced under strict, measurable standards that he enforced directly.

In the years that followed, he applied the same mindset that had governed his scientific work. Milling machines were introduced to engrave lettering along coin edges to expose tampering. Hammered coinage was scrapped in favour of screw presses that produced sharper designs and consistent weight.

“The coins had to be minted to a much greater degree of exactness than was ever known before.”

— Isaac Newton, Royal Mint Reports, 1701

He cut weight deviations nearly in half and refined the Mint’s assaying methods to catch any inconsistency in metal purity.

Quality control was constant. The Trial of the Pyx—a centuries-old public process where samples of newly minted coins were weighed, tested, and inspected for purity against official standards—was enforced rigorously, and he demanded regular testing of samples drawn from production batches. Every detail had to match the standard to a T.

In 1717, he issued one of his most consequential rulings: fixing the value of the guinea—a gold coin introduced in the 1660s that had long traded above its face value—at exactly 21 shillings.

“A gold coin was worth 21 silver shillings.”

— Isaac Newton, Letter to the Lords Commissioners of His Majesty’s Treasury, 1717

This effectively priced silver out of the market and shifted the foundation of Britain’s currency to gold. The policy wasn’t passed through Parliament, but the ratio was enforced at the Mint. From that point forward, England functioned on a gold standard in practice, even before it was declared in law.

Newton’s approach to money was shaped by the same mindset that guided everything else he did—precision, order, and strict adherence to measurable reality.

He didn’t see currency as something governments could manipulate at will, but as something that had to reflect the actual metal it was made from.

If a coin said it was worth a shilling, it needed to contain a shilling’s worth of silver. Anything else was fraud. He didn’t spend time writing economic theory because he didn’t need to. His reforms at the Mint were a direct application of the same principles he used in science—if something couldn’t be weighed, measured, or verified, it had no place in the system.

Later economists like Adam Smith would take many of the same ideas and build upon them, often without mentioning where they came from.

Newton had no interest in theory for its own sake. He cared about building systems that couldn’t be gamed.

So when a forger as bold as William Chaloner started using Parliament, pamphlets, and public accusations to force his way into the Mint, Newton made it personal. What followed was one of the most methodical takedowns of a criminal operation in British history.

The William Chaloner Saga

By the late 1690s, Newton had full authority over the Mint and was trying to stabilize an institution riddled with dysfunction.

But one name kept coming up—William Chaloner. He had already made a fortune forging coins, lottery tickets, and banknotes. Once established, he shifted tactics. Chaloner began printing pamphlets accusing Mint officers of fraud and used those accusations to pressure Parliament into giving him a seat at the table.

The accusations gained enough traction that Newton was ordered to hear him out.

He listened, dismissed it immediately, and started building a case. Without ever responding publicly, he went to work behind the scenes, pulling testimony from inside Chaloner’s network.

He tracked down metalworkers, handlers, and middlemen, linking names to tools, addresses, and forged coins already on the streets.

He tracked who was supplying dies, who was casting blanks, and where the operations were being run.

Much of the evidence came from informants who had worked directly with Chaloner and were now willing to testify.

Others were pressured into cooperating through targeted interrogation and cross-examination.

Newton even went so far as to go undercover himself, putting on disguises, gathering information in taverns and among known forgery circles.

He documented everything—depositions, coins, samples, tools—and assembled it into a case strong enough to push past Chaloner’s political protection.

Under mounting pressure, Newton prepared the final case for Chaloner’s prosecution. By early 1699, he had secured enough witness statements, physical evidence, and supporting testimony to formally charge Chaloner with high treason.

Chaloner tried to stall the inevitable—claiming illness, then insanity—but it didn’t matter. Newton had already linked him to specific coining setups, forged dies, and the bribery of key witnesses. The evidence was too solid to brush off.

The trial was set for March 3, 1699, at the Old Bailey, London’s main criminal court. Newton didn’t appear in person, but every detail of the prosecution’s case had his signature on it.

Newton’s case was airtight. He had flipped key witnesses, traced entire operations, and matched forged coins directly to Chaloner’s moulds. The trial moved quickly. Former accomplices took the stand one after another, each confirming Chaloner as the one supplying the tools and running the operation.

Chaloner was convicted of high treason and sentenced to death. In the days leading up to his execution, he sent letter after letter from Newgate Prison—denying everything and begging Newton for mercy. Newton never responded.

On March 22, 1699, Chaloner was taken to Tyburn and hanged in front of a crowd. It marked the end of a three-year pursuit that remains one of the most relentless and well-documented manhunts in English history.

Newton and the South Sea Bubble Collapse

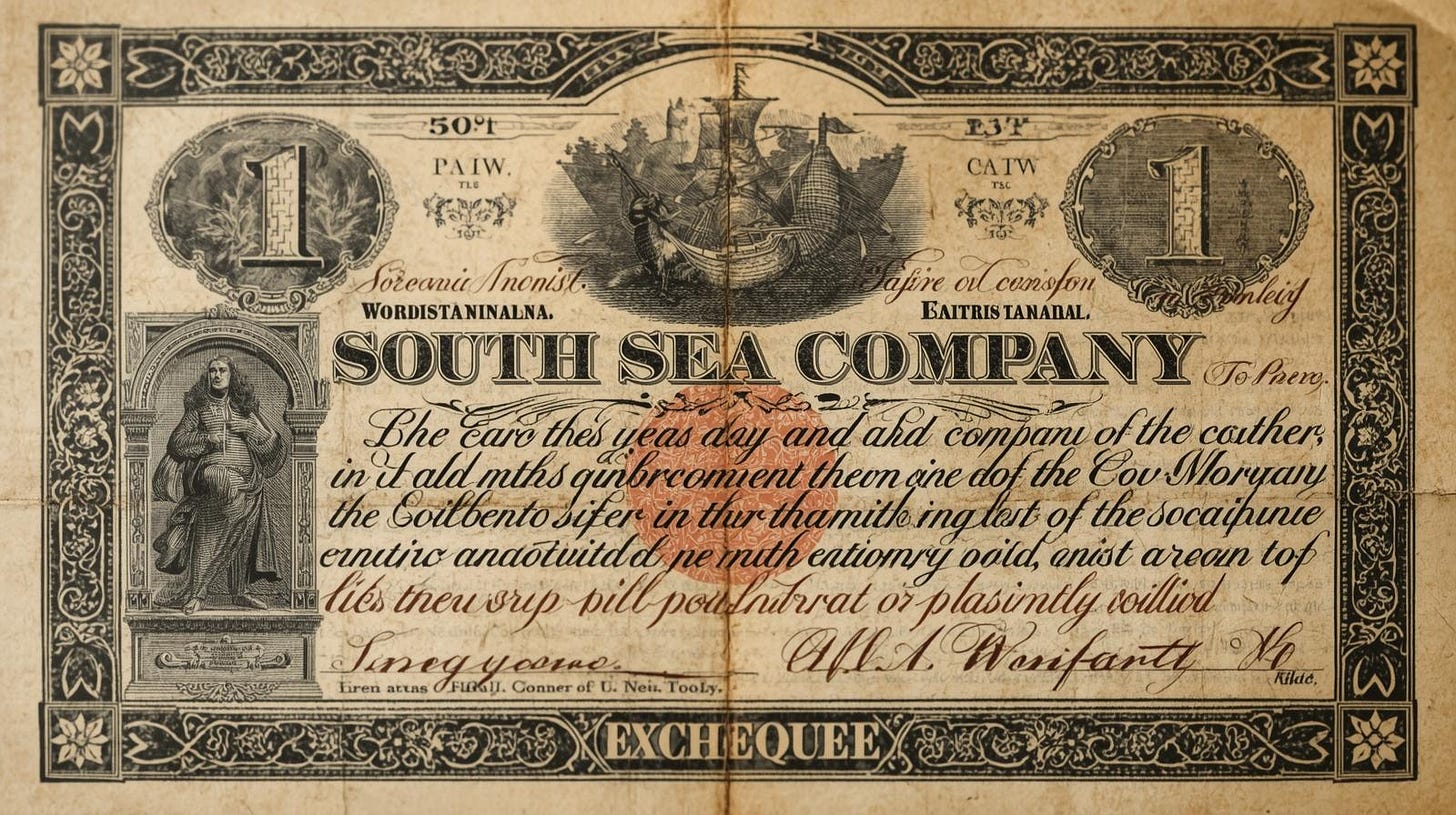

In 1720, Newton got caught up in one of the biggest financial disasters in British history—the South Sea Bubble.

The South Sea Company had been sold to the public as a gateway to untapped riches in South America, mainly through the slave trade with Spanish colonies.

The company was a front for a government-backed debt conversion scheme, kept alive by political bribes, insider trading, and pure speculation. It had nothing to do with value and everything to do with hype.

In 1720, South Sea shares exploded—from £128 in February to over £1,000 by August. Behind the scenes, members of Parliament were knee-deep in it, while the people meant to regulate the market looked the other way.

When it collapsed, it unravelled fast. Investors were wiped out. Banks failed. Parliament scrambled to contain the fallout and launched an inquiry. A handful of directors and politicians were stripped of their assets and banned from office. Most walked away untouched.

The fraud was too big and too public to ignore. Parliament opened an inquiry to contain the fallout and settle public outcry.

Newton saw what was coming and sold early, walking away with about £20,000. But as prices kept rising and the hype kept spreading, he bought back in—this time near the top. When the final collapse hit, most of his gains were gone.

Had he just held his original position, he would’ve walked away with more than £50,000. In today’s terms, that’s the equivalent of roughly $10 million USD. Instead, he joined the list of those who got wiped out. Afterward, he said,

“I can calculate the motions of the heavenly bodies, but not the madness of people.”

Newton saw through all the noise to find what was intrinsic to reality. Forget philosophy, forget what the so-called authorities say about falling objects or moving planets. The universe had its own instruction manual, written in math and physics. Newton just learned to read it.

Money should require the same treatment. Ditch the systems built on false promises and the ever-shifting power struggles at the root of political corruption. Real money should be as predictable and unchangeable as the laws of physics.

Measurable energy. Unbreakable code. Time is moving in one direction only. In part two, we’ll explore whether Bitcoin represents exactly this—the discovery of what money looks like when it obeys the same fundamental rules that govern everything else.